On a hot August day in 1071, on an arid upland valley in Armenian, the Eastern Roman/Byzantine army marched out of camp to battle the forces of the Seljuk TurkishSultan, Alp Arslan. There, near the town of Manzikert, the course of medieval history and the map of the Near East would be changed forever. It was a seminal moment, that would set in motion a chain of events whose impact is felt to this day.

The Eastern Roman Empire was the strongest and most developed nation in Europe and the Near East. (The term “Byzantine” was an invention by later historians, and would have seemed bizarre to the men of the time, who thought of themselves as “Romans”, and their land Romania. In Greek, the language of the Empire, their realm was called Basileia Rhōmaiōn; and in the West was referred to in Latin as the Imperium Romanum.) It possessed the only truly professional army in the world, the linear descendant of the armies of the Caesars. At its greatest extent, under the Emperor Justinian in the 6th century, the Empire had stretched from Spain to the Euphrates River.

However, since the Muslim conquests of the 7th century, the Empire had shrunk to an area encompassing the Balkans in Europe, and the Anatolian peninsula in Asia. Under the warrior Macedonian Dynasty of emperors, the Romans had pushed back in both the east and the west. Only two generations earlier the “hero Emperor” Basil II had pushed the borders of the empire to their largest extent since the days of Justinian (see “Greatest Commanders of the Middle Ages“). The Muslim Emirates of Eastern Anatolia had been conquered and all of Anatolia was reclaimed for the Empire. Armenia, long a battleground between Rome and whatever power ruled in Persia, was again part of the Empire. Even southern Italy once again bowed to the Emperor in Constantinople.

However, since the death of Basil II in 1025 the Empire had been in a slow but steady decline. Civil wars had wracked the empire, and two unofficial factions had developed in the capital whose partisanship would ultimately undermine the Empire’s strength.

One was the “Soldier’s Party”, which stood for a strong defense and championed the cause of the small farmers of the countryside; who formed a semi-professional militia force that was the backbone of Imperial defense. Its chief members were the great families of the provinces (called “Themes”); who were also the strategoi (generals) of the provincial armies. The other was the “City Party”, of the wealthy aristocrats and members of the civil bureaucracy who lived in or around the capital, Constantinople. These resented the high cost of maintaining the superb, professional forces that defended the provinces. With Constantinople itself protected by the most massive and comprehensive defensive walls in the world, the dandies of the city felt secure enough, and had little concern for what occurred in the distant provinces.

This factional infighting led to a cycle of civil war; with provincial generals marching periodically on the capital to replace the current occupant of the palace. Win or lose, soldiers died and the empire was weakened. When the City party was again in power, it retaliated by disbanding native units, increasing taxes on the provincials (which drove many of the small landowners to financial ruin, thus reducing the supply of regular troops to the army); and replacing native Roman regiments, which might rebel at some future date, with foreign mercenaries without political interests. Under Constantine X Doukas, an emperor of the City Party, the army that garrisoned and defended Armenia, on the embattled frontier with Islam, had been disbanded; along with many of the regiments of other Themes.

Meanwhile, on the Empire’s eastern frontiers, the rival Islamic Caliphate was now home to a new warrior race: the Seljuk Turks.

Established in the wake of conquest which followed the death of Mohammed in the early 7th century, the Caliphate was the other great power of the Middle East. These two super powers of the day were often at war; and the border regions between them were the scene of regular raid-and-counter-raid by Christian Akritai and Muslim Ghazi.

The Turks were newcomers to the scene. A nomadic people, they had migrated several generations earlier from their homelands on the Central Asian steppe. Arriving in the lands of the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad, the Turks had converted to Islam, and become eager warriors of the Prophet.

Successive Caliphs had enrolled the warlike Turks as mercenaries into their armies. In time, these Turkish mercenaries became the strongest force in Islam, and had supplanted the secular authority of the Caliph with that of their own Sultan; relegating the Caliph to the position of religious figurehead. (In several ways this arrangement between Turkish Sultan and the Abbasid Caliph in the 11th century mirrors that of the Japanese Samurai Shogunate with the Mikado, the Japanese Emperor.) Thus, by the 11th century A.D., the Abbasid Caliphate of Bagdad had become overlaid by the Seljuk Turkish Empire.

Filled with all the zeal of new converts, the Turks happily conducted jihad upon the neighboring Christian Roman Empire. The usual situation of low intensity raids-and-reprisals along the border grew larger and more dangerous. Turkish forces penetrated deep into Anatolia on several occasions, finding the interior of the Roman provinces rich pickings; their garrisons reduced in strength by decades of military cuts by the bureaucrats in the capital. In 1067 the ancient city of Caesarea (formerly Mazaca in Cappadocia), capital of the Charsianon Theme was sacked by one of these deep-penetrating Turkish raids; and the population was massacred. Three years earlier, in 1064, a large Seljuk army, led by their Sultan Alp Arslan, attacked the Armenian capital of Ani; now deserted by its Roman defenders. After a siege of 25 days the Turks captured the city and slaughtered the population. An account of the sack and massacres is given by an Arab historian:

“The (Turkish) army entered the city, massacred its inhabitants, pillaged and burned it, leaving it in ruins and taking prisoner all those who remained alive…The dead bodies were so many that they blocked the streets; one could not go anywhere without stepping over them. And the number of prisoners was not less than 50,000…”

Then in 1068 a new soldier Emperor took the imperial diadem. A leader of the Soldier’s Party, Romanus IV Diogenes gained the throne by marrying the widowed Empress Eudoxia. Her late husband, Constantine X Dukas, had left a 17 year old son, Michael VII, as heir to the throne. However, young Michael Dukas had shown little inclination or ability to rule. At his mother’s marriage to Romanus, Michael was relegated to the position of powerless “co-Emperor”.

The Dukates were a leading family of the City Party, and deeply resented Michael being supplanted by his mother’s new husband. Though they were unable to prevent Romanus’ accession to power, they were determined to undermine his reign. Romanus was aware how precarious was his perch, which could only be made secure by a military victory: as a hero-emperor he could stand against the Doukates on his own. In 1070, he decided to stabilize the eastern frontier by means of a massive military response to the constant Turkish raids; one that would drive the invaders out of Roman lands for a generation.

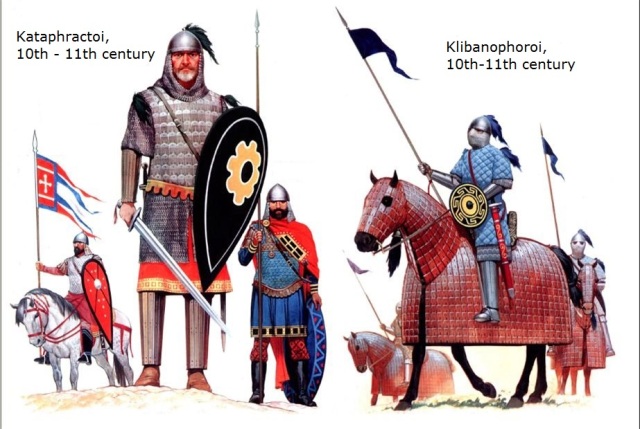

Regular Byzantine soldiers, 10th – 11th century

Romanus spent the year mustering troops from all over the Empire, assembling the combined forces of the European and Asiatic Themes: the Banda (companies) of professional kataphraktoi, the heavy cavalry that were the backbone of the imperial army. In personal attendance upon the Emperor were those Imperial Guard regiments were stationed in or around the capital, Constantinople. These were collectively referred to as “Tagmata”. Mostly comprised of regiments of kataphractoi, these also included units of klibanophoroi, the

super-heavy armored lancers that were the iron core of the emperor’s strike force. Many of these guard regiments dated back to the Emperors Diocletian and Constantine, but a more recently raised force was the storied Varangian Guard. Raised by Basil II, these were axe-wielding Scandinavian and Russian heavy infantry, much feared and respected in the east; and formed the Emperor’s personal bodyguard.

The total Roman force Romanus took east was 60,000 strong; and represented nearly every soldier available to the Emperor at the time. To appease his Dukate rivals, he was forced to appoint as his second-in-command youngAndronikus Dukas; cousin of his co-Emperor, Michael. A young dandy of the city devoid of military experience, this promotion of a political enemy to high command was to have disastrous results in the coming campaign.

The year 1070 was spent chasing small bands of Turkish raiders out of

Anatolia; the army advancing ever eastward. By summer of 1071, the Imperial army had reached Armenia: a land of high hills and long, deep valleys. There, Romanus split his army. While he and the largest part marched on the fortress town of Manzikert, Romanus detached a strong force of Roman regulars (perhaps including some of his Varangians), and Pecheneg and Normanmercenaries to besiege the fortress of Chliat, a day’s march away. Manzikert was easily captured on August 23, and Romanus camped in the valley and waited for Chliat to fall and that detachment to return.

Unbeknownst to Romanus, the Turkish Sultan and his army were at that very moment marching directly upon him. Earlier in the year, Alp Arslan (“The Mountain Lion”) had made peace overtures. But Romanus needed a victory, not a negotiated settlement. He rejected the Sultan’s offer, and now Alp Arslan was coming to give Romanus what he desired: a great and decisive battle.

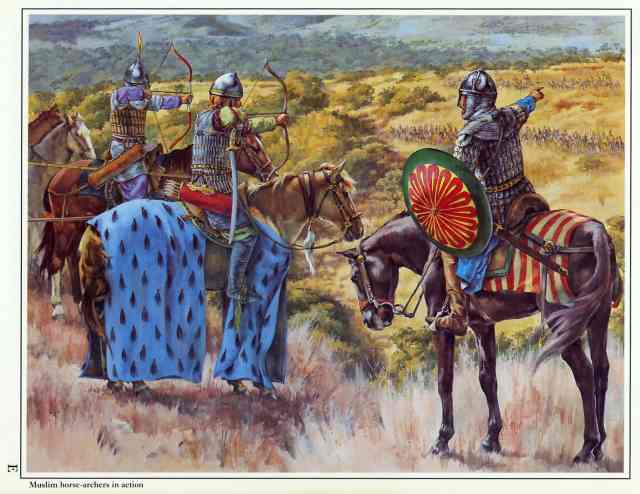

Roman scouting was unaccountably poor, and the first indication the Romans had that a large Turkish army was in the vicinity was when foraging parties were driven-in by lage parties of aggressive Turkish horse archers. A considerable force of Roman regular cavalry, under Basilakes, Dux of Theodosiopolis (a Roman fortress town near the eastern frontier, now the modern Turkish Erzurum) was dispatched to drive off what was thought to be just bands of Turkish raiders. Instead, Basilakes blundered into the Sultan’s army, and his force was annihilated.

Another contingent under Nikephoros Byrennios, commander of the forces of the European Themes, was dispatched to aid Basilakes. These too were roughly handled, and retreated back into the Imperial Camp.

As swarms of Turkish horsemen poured into the far end of the valley, the Emperor and his commanders realized this was no raiding force, but the Sultan’s main army.

The Sultan now sent a delegation to request a cessation of hostilities; but, as earlier in the year, Romanus rejected this overture. Sending messengers riding post haste to Chliat, Romanus prepared to give battle the next day.

The following morning, August 26th 1071 the last great native Roman army the Empire would ever field marched out of camp and deployed for battle.

Facing them was a cloud of some 40,000 Turkish light cavalry horse archers, led by Sultan Alp Arslan. The exact size of the Roman army on the field is unknown. Though originally 60,000 strong, the detachment sent to Chliat (whose size is unclear) and the loss of Basilakes force had reduced this figure. Now the armies opposed may have been roughly equal.

The Romans deployed in the usual formation recommended by their tactical manuals when facing swift-riding nomadic horse-bowmen: two divisions in line, one behind the other, a bowshot apart. Though it is not stated, each of these lines was comprised of 3-6 ranks of horsemen. The first line advanced steadily against the enemy, attempting to come to close quarters if possible; but maintaining an advancing wall of armored men and horses, forcing the lightly armed and largely unarmored nomads to fall back. The second line was to follow the first, preventing its encirclement (the favorite tactic of the steppe nomad, utilizing their speed and mobility to encircle and attack from flank and rear slower-moving formations). Should the Turks get behind the first line, the second line would then charge those enemy forces; sandwiching and crushing them like a nut between the twin arms of the cracker!

At Manzikert, the first line was comprised of the Tagmata, regiments of elite guard troops, in the center and the professional cavalry troopers of Europe and Asia on either flank. The Emperor himself commanded this division, from the center, surrounded by his guards and beneath the sacred, gem-encrusted banner of Christian Byzantium, the Labarum (first carried by Constantine the Great at the battle of Milvian Bridge).

The second, supporting division was composed of the feudal retainers of the great landed gentry of the eastern frontiers. Much like the feudal men-at-arms of their counterparts among the Franks to the west, these troops varied in quality; but all were armored cavalry capable of giving a Turkic nomad an even fight.

This was a textbook plan, as taught by Byzantine manuals such as “The Tactica” of the Emperor Leo the Wise; proved over centuries of warfare to be the most effective way of defeating nomad horse archers. The weakness in the Emperor’s deployment was political, not military: Andronicus Dukas, his political enemy, was given command of the tactically vital second line reserve.

All that long, hot August day the steel-clad Roman horsemen advanced up the highland valley. Tantalizingly just beyond the reach of their lances, a cloud of Turkish horse-archers continued to skirmish. Arrows flew back-and-forth, doing little damage to either side. The Turks refused to stand against the mailed Roman bands, and all day continued to fall back before the Byzantine advance; exchanging arrows but refusing to come to grips. By mid-afternoon the Roman’s passed over the campsite occupied that morning by the Sultan’s army. Still the enemy fell back down the long valley, loosing arrows as they withdrew.

Casualties were likely few on either side during the day-long, rolling skirmish battle. The Romans were well armored, and few of the light Turkish arrows would have wounded or killed a man. Roman arrows fell among the loose-ordered and constantly boiling ranks of the Turks, often as not missing their rapidly moving targets.

Near evening, frustrated by the Sultan’s unwillingness to come to grips, the Emperor ordered the Roman bands to wheel-about and return to camp.

No sooner had they shown their backs to the enemy than, kettle drums booming, the Turks closed-in like a pack of wolves.

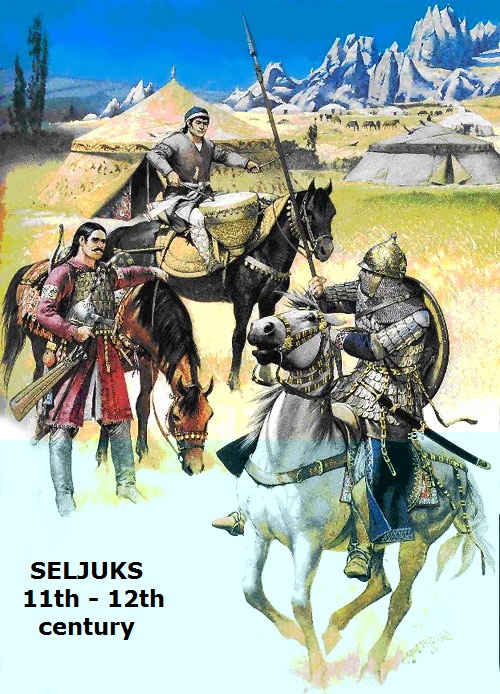

Seljuk soldiers

For the next hour the Romans retired towards their camp, the Turks pressing hard upon their rear. The Romans were able to keep their enemy at bay with controlled “pulse charges”, in which individual “Banda” (companies) of Romans would suddenly wheel about and charge the Turks who were nipping at their heals. The Turks would scamper off on swift ponies, out of range to regroup, while the charging Roman band would return as quickly to its place in the retreating line. Only the best drilled and disciplined soldiers in the world would have been capable of such maneuvers. It is a testament to their quality that though greatly stressed by the factional strife that ripped the Empire throughout the century, the Roman army was still capable of this, the most difficult of maneuvers.

View of the battlefield from the rising ground to the south. It was from here that the Sultan viewed the oncoming Romans and the slow withdrawal of his horsemen before them. It was in the flat ground in the center of the picture that Romanus ordered the Byzantine forces to “about face” and return to camp; precipitating the Turks to take the offensive.

Toward sunset, the Turks seemed to make a mistake: around both ends of the retreating Roman first line, hordes of Turkish riders swarmed; into the space between the first and second lines, in an obvious attempt to separate them and destroy the Emperor’s first line in detail.

For Romanus and his tired troopers, opportunity had come at last to smash the impudent rascals! Imperial trumpets blew the order, calling for the still retreating second line to halt, wheel-about in-mass, and smash the foolish interlopers between the two iron-clad divisions of the army.

Instead, to the dismay and growing horror of the soldiers of the Emperor’s division, the second line continued to withdraw from the battle. Either because he misunderstood the order (unlikely), or willfully and treasonably disobeyed it, Andronicus Dukas led the second line off the field; abandoning the Emperor and the professional regiments of the Eastern Roman Empire to their fate!

(The Dukates would later defend Andronicus’ actions by claiming that Romanus and the first division was hopelessly cut off and doomed. That Andronicus was wise to save what he could of the army; refraining from what amounted to throwing good money after bad. This argument, however, is all too self-serving to be convincing.)

The first division found itself surrounded and attacked from all sides. All order and command-and-control vanished, as the battle dissolved into swirling chaos. First the right wing, composed of the troops from the Themes of Anatolia (the senior regiments of the army) broke and fled back up the valley. This freed more Turks to join those swarming around the armored guard regiments massed around the Emperor’s standards. Then the left wing, the Thematic regiments of Europe, cut their way out of the encirclement, seeking refuge in the nearby hills.

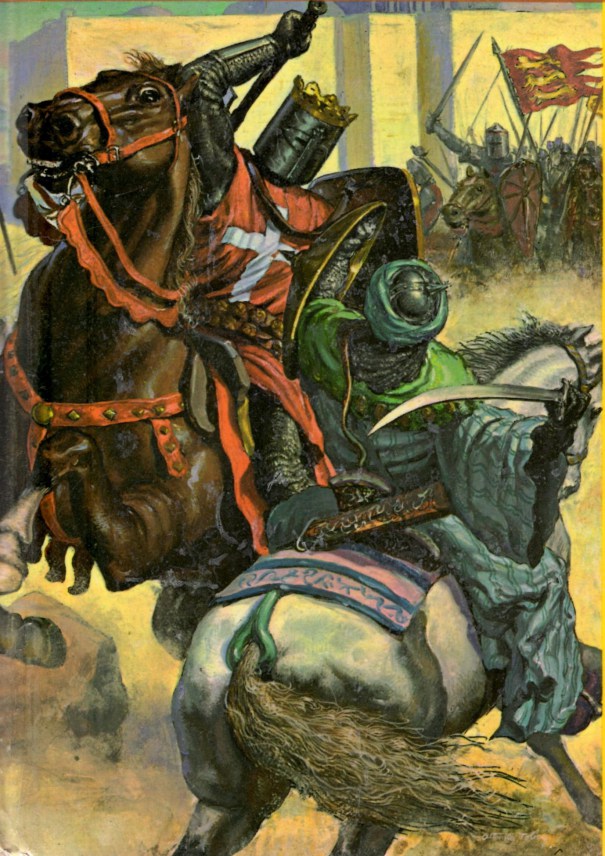

The Sultan Alp Arslan had known from the beginning that at some point he would have to fight the Romans at close quarters in order to break them and gain a total victory. Now, as chaos reigned in the Roman ranks, the Sultan put aside his gilded bow and drew his mace (the favorite weapon of Turkish heavy cavalry). Surrounded by the armored Ghulams(slave-soldiers) of his personal guard, he now charged into the center of the Roman masses; where the Emperor could be identified, still fighting, surrounded by his Varangians beneath the holy banner of the Labarum.

The fighting was vicious and at close quarters, and the weary and outnumbered Romans were overpowered. Romanus was captured, trapped beneath his fallen horse. He was taken before the Sultan, who treated him as a guest; not a prisoner.

Romanus was held only a few days, before being released by the Sultan. The defeated emperor returned to find the Dukates in rebellion; with young Michael VII now declared sole ruler. In the resulting civil war, Romanus was captured and blinded by the vengeful Dukates; in such a severe fashion that he died of the injury.

The immediate result of that “Terrible Day” at Manzikert was the loss of Anatolia, the Asiatic heartland of the Roman Empire. As the Romans fought each other over the next decade, clans of Turkomens migrated and settled all throughout the Anatolian plateau; encouraged by the Sultan to take the land and make war on the Christians. By the timeAlexios Komnenos had consolidated power and established a new dynasty in 1081, the damage was irreparable; and the Turks would never be driven from these lands again.

From these provinces had come the best troops in the Empire, as well as most of the tax revenue to maintain a professional army. Without either, the Byzantine Emperors were never fully able to replace the army lost that day. For the remaining centuries of its declining existence, the Eastern Romans would be forced to rely largely on mercenary soldiers, of often dubious quality and loyalty, to fight its battles.

The Byzantine/Roman army had for centuries shielded the West from the forces of militant Islam. Without this bastion, the West would have to rise up and provide its own military response to the march of Islam: the Crusades. To this day we still feel the echo of those distant centuries of conflict. The hatreds and paranoia engendered by those wars between Christian Europeans and Muslims still affect relations between the Islamic World and the West today.

Anatolia, once the heart of the Hellenized Roman east, became after Manzikert a vast arid steppe; as the Turks deliberately turned farmland into pasture, and cities into rubble. And Romania became Turkey; which it is to this very day.

Another, sobering lesson of Manzikert is pertinent to America today. When factional hatred is so great that defeating ones domestic political opponents at home is more important and desirable than winning a war against a deadly enemy abroad; any treason is possible to further that despicable cause. Certainly the partisans of the House of Doukas never accepted their responsibility for the disaster at Manzikert. The defeat of their political rival, Romans Diogenes, justified in their minds betraying the Empire they served.

The result was a catastrophe from which the Roman Empire in the East never recovered.

Σχετικά με τον συντάκτη της ανάρτησης:

Η ιστοσελίδα μας δημιουργήθηκε το 2008.Δείτε τους συντελεστές και την ταυτότητα της προσπάθειας. Επικοινωνήστε μαζί μας εδώ .

κανένα σχόλιο